A two -year long legal battle pitting former South African and Rhodesian mercenaries, playing out in South African courts, could throw significant light in events, people at the tail end of the war of liberation – or the Rhodesian Bush War in the late 1970s.

General Peter Walls is accused of having had prior knowledge of the infamous downing of a civilian plane; Rhodesian Forces were responsible for anthrax attacks on black people and Rhodesian some excursions in Mozambique ended ignominiously, while the settler forces were informed by “wrong theories”. Further, the Rhodesian army has been revealed to have been in a shambles, not professional hotshot, and relied on mass killings of blacks.

The High Court in Pretoria is hearing a case in which former soldiers are trading accusations on an abortive mission by the Rhodesian forces.

The parties are Brian Carton-Barber of 91 4th Avenue, Northmead in Benoni near Johannesburg, and Ian Bate of 17 Stableford Road in Randpark also near Johannesburg.

Carton-Barber who is the Applicant, is a former South African mercenary who served in the former Rhodesian Light Infantry under command of the Ian Smith regime. At the time of the incident that ultimately led to the court case he was a lieutenant, whilst Bate, the Respondent, was the RLI commanding officer with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Carton-Barber is the nephew of Jack Carton-Barber who became famous whilst serving in Mike Hoare’s mercenary army that served in the Congo under the direction of Moise Tshombe. Before volunteering for service under Smith, Carton-Barber was an officer in the South African Army and served in Angola and Namibia. He joined Smith’s forces in 1977.

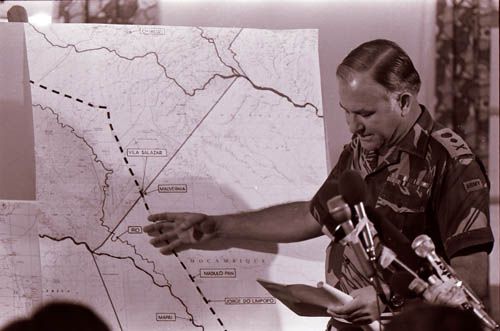

According to the court papers Bate ordered him to participate in Operation Inhibit. This was in 1979 and was an effort designed to isolate the town of Malvernia in Mozambique. The plan was to deny facilities to ZANLA forces. From the Rhodesian perspective the operation carried a hoodoo, for not only was the operation a complete failure but it led to three deaths in another participating unit, the Special Air Service. The court documents assert that Bate was furious at the RLI failure, and dismissed Carton-Barber from the regiment on the pretext of his having displayed cowardice in the face of the enemy. The same documents refute this, listing a serial of blunders that constituted a level of Rhodesian military incompetence certainly not spoken of in the post Chimurenga books written by and read by former Rhodesians. Bate, according to Carton-Barber, was central to this incompetence, but chose to deflect from his deficiencies as a military commander by laying blame on a junior officer (Carton-Barber) instead.

Another figure listed in the documents as not being the brilliant soldier he still is held up as, is Patrick Armstrong who was Bate’s deputy at the time of Operation Inhibit. Armstrong supported Carton-Barber’s dismissal for alleged cowardice. The former man had been decorated by the Smith regime through being made an Officer of the Legion of Merit. The award is senior to the bravery award, the Bronze Cross of Rhodesia, but the RLI history, a book called “The Saints,” copies the official award citation. It states part grounds for the award as Armstrong’s “superficial but painful” wounding by a few pieces of plastic. Armstrong was to be promoted to commanding officer of the Selous Scouts. At the time of both the award and promotion, Armstrong was dating a daughter of the Rhodesian military supremo, Lieutenant General Peter Walls. The couple were to marry and now reside at 11 6th Street, Houghton in Johannesburg

In Carton-Barber’s submissions to the court, he states that as a result of the now ignored but ignominious defeat of the Rhodesian forces on the outskirts of Chicualacuala, that a number of RLI troops were so shattered by the experience as to mutiny. Both Bate and Armstrong have denied this under oath, but the statements are in conflict not only with their formal admissions that the troops had refused orders, but with the Rhodesian Defence Act and its successor (the Zimbabwe Defence Act).

Both define mutiny as a refusal of orders. As pointed out by Carton-Barber, both pieces of legislation require senior officers to suppress mutiny, something no one in the RLI nor the rest of the Rhodesian Army saw fit to do. He states further that his requests for a court martial to test the allegation of cowardice in the face of the enemy, were denied. One has to ask what the effects on the white minority should have been, had the mutineers been charged as the law dictated? In other words, that the Rhodesian Army should have been exposed for the fraud that it was? Bate has expressed that Carton-Barber’s dismissal was “in the interests of my regiment.” Carton-Barber in a statement to Review and Mail has indicated that he intends asking Bate for clarification and meaning of these “interests” when the court matter is heard.

Although these military events occurred a long time ago, they are not without legal consequence as Carton-Barber states that he learned of broader facts only recently. It was this fresh knowledge that enabled him to approach the courts. His posting from the RLI was followed by one to Headquarters Midlands District in Gweru, where he was a staff and not a field operative. Yet it was the very nature of his headquarters duty that exposed him to very disturbing developments in the war. Carton-Barber has told Review & Mail that although it took years for him to “connect all the dots,” that he was aware of the levels of desperate depravity to which the Rhodesian regime would stoop in its frustration at losing the war.

An important dimension was the anthrax pandemic that seized rural Zimbabwe in 1979. Many observers have suspected that it was engineered by Smith’s government, but little in the way of first hand evidence has emerged. Until now. Carton-Barber has disclosed to Review and Mail that anthrax investigators have misdirected their enquiries. The reason is that these enquiries were aimed at a Rhodesian Army formation called Psychological Operations, or Psyops. This body inadvertently has been confused with a similarly named but different civilian agency called Psychological Action, or Psyac.

It was Psyac, according to Carton-Barber, who coordinated the spread of anthrax spores in the Tribal Trust Lands. He states further that the Rhodesian Veterinary Department were the physical cultivators of the spores. He admits that he cannot speak for the country beyond the Headquarters Midlands District zone of authority, but that as far the zone itself was concerned, that light civilian type aircraft flying from Thornhill Air Force Base ferried the spores to target destinations within the zone

“I ought to know,” he said, “because my task was to log the flights.” He says that the reason for this biological warfare programme was firstly to create a massive outbreak of anthrax infections, and secondly that Psyac leverage of the media could bring the disease spread to public attention. The theory was that intended and actual guerrilla incursions to rural areas then would be upset due to fear of the disease. “The point,” he goes on to say, “was the fact that the security forces had lost control of the war.”

The reason why he has included these facts in the court papers is to present the culture of illegality that motivated Smith regime action. Allied to this is that it contextualizes his illegal dismissal from the RLI as also impacting on the illegal condonation of mutiny within that regiment. Bate’s papers state that the adjutant general of the Rhodesian Army supported Carton-Barber’s dismissal from field command. “I was given no opportunity to defend myself,” the latter tells Review and Mail.

“The army was following its own shadowy agenda of self preservation in order to mislead the country and the world. What happened in the process was that the army mislead itself into believing that it was professional and hot shot. It wasn’t. It was a shambles that resorted to mass murder of tribespeople.

Carton-Barber has told Review & Mail that as a member of a Rhodesian headquarters, that he was present at briefings where it was disclosed that several so called “terrorist atrocities” actually were the work of the Selous Scouts.

Again there was an underlying theory. It being that because the Selous Scouts were posing as members of the guerrilla movements, that victims would develop antipathy toward those movements.

A parallel was that international perception also should sway sympathy from the liberation forces toward the Smith government

As it turned out though, tribespeople were not the only ones to suffer cold blooded murder by Rhodesian troops. Whilst at Gweru, Carton-Barber was tasked to investigate why no guerrillas were being captured in RLI “Fire Force” actions.

The concern hinged on the fact that Rhodesian intelligence harvesting was being starved. His conclusion was that the “enemy” wounded and those willing to surrender were being shot out of hand in violation of international law.

His report was rejected by Headquarters Midlands District, but after the war “The Saints,” a Rhodesian history book was to throw light on what was afoot. There is a bald admission that a sort of policy not to take prisoners existed.

Feeble excuses are tendered, but there is a reference to the anger that greeted the well known downing of a Viscount airliner on 12 February 1979.

What stands out though, in Carton-Barber’s view, is that such a policy was self defeating because it did rob the Rhodesian Army of information that might have been obtained from prisoners. “It was a blood lust attitude that ironically contributed to the Rhodesian defeat,” he tells Review & Mail

His discomfort at the take no prisoners approach is moulded by a personal experience. Whilst with the South African Army in Angola he witnessed allied UNITA soldiers cut the throat of a surrendered Cuban soldier.

The episode left an emotional mark, because Carton-Barber thought that if he’d been taken prisoner that he’d have expected to be treated in accordance with the decency of international norms. Neither the RLI nor it’s officer hierarchy had any qualm about disregarding the “civilized” values they pretended to be upholding.

Of course it’s impossible to determine the statistics of these war crimes, but Carton-Barber can’t be far off his estimate of “hundreds” of dead. Neither can he be wrong when he says that, “The RLI’s reputation for proper and acceptable military effectiveness is nonsense. I don’t deny that there were times when they were highly efficient, but they often behaved like a collection of thugs given free rein by leaders of doubtful professional and human quality. In the final analysis wanton murder cannot be portrayed as legitimate battle success. It’s a falsehood, one being perpetrated to this day”

What passed for Rhodesian “strategy” was borrowed in part from Americans in the Vietnam War. There it was called the “body count,” a notion that battlefield success could be measured in the amount of casualties inflicted.

During the Second Chimurenga, the Smith regime and its generals like Peter Walls referred to what came to be known as the “kill rate.” Here too was a theory, it being that the sustaining of disproportionate fatalities indicated that the war was being “won.”

So long as this rate was favourable to the Rhodesian Army, so could the regime claim that it was in control and that the liberation armies were being defeated. Walls alluded to this in public statements made in South Africa where later he settled.

What he chose not to say was what grounded this propaganda. The reality was that the propaganda was relayed to the world via a secret policy of not taking prisoners. It was aimed at fooling everyone into the false belief that the “kill rate” goal actually was being achieved in security force “effectiveness” and liberation army “incompetence”.

“Effectiveness” was an outright lie, but Walls can be measured by his dirty hands that were to drip blood elsewhere.

It involved the downed Viscount of 12 February 1979 that partly “justified” the take no prisoners policy. To this day whites regard the Viscount incident with angered distaste, but remain ignorant of the background and especially the direct role of Walls in the tragedy.

The truth finally has emerged in the Pretoria High Court documents.

In August of 1978 and on order of Walls the Rhodesians attacked a ZANLA base with paratroopers.

Some of these paratroopers were airlifted in DC7 aircraft, a four engined aeroplane not used by the Rhodesian Air Force but on charter for what was codenamed as Operation Mascot.

The DC7 has a resemblance to a Viscount, and this led to a liberation army mistake that although tragic is understandable. The error lies in the conclusion that Viscounts had been used for the paratroop assault, and the fist Viscount downing (on 3 September 1978) was viewed by liberation fighters as legitimate retaliation for Mascot that took place shortly beforehand.

See also Part 1 & 2

No one disputes that the loss of the Viscount was a tragedy, but no one from the Smith regime has answered the question of why civilian aircraft that resemble Viscounts were chartered for military attack purpose to begin with. This brings us to the second Viscount that was shot down

On the evening of 12 February 1979 there were two Viscount flights from Kariba to Harare (then Salisbury). Liberation force intelligence had learned that Walls was scheduled to fly on the fist aeroplane to take off and despite what whites think, he was the target.

Shortly before boarding however, Walls was tipped off by his own intelligence sources who had learned of the liberation army plan to kill him. He then betook himself to the safety of the second flight, and true to the war criminal that he was, took no action to prevent the first flight and the deaths that followed. His motive, apart from saving his own skin, was to protect his intelligence source.

He might even have gotten away with his cowardly deed, but he made a mistake

One of his daughters, a sister to Pat Armstrong’s wife, was Second Lieutenant Valerie Walls of the Rhodesian Women Service.

Still resident in Harare, she then was stationed at a military barracks called KG6. Realizing that news of the Viscount downing was going to break, Walls phoned the barracks and ordered that his daughter be informed that no matter what she heard, that he was alive and safe.

Walls’ mistake was twofold. First was that his message passed through a relay of soldiers, some of whom since have spoken, and second was that he used an open and therefore insecure telephone line. Intelligence operatives from various international agencies tape recorded the message

“Whether one speaks of Rhodesia or Zimbabwe,” Carton-Barber carries on, “or of the Rhodesian War or Chimurenga, what stands out is that it utterly disproves the superiority of the white man over the black.

“There is this hidden record of mutiny in an elite unit, of anthrax and of shooting wounded men unable to defend themselves. There’s the Walls’ culpability for the shooting down of a Viscount. This is the true legacy of whites in Zimbabwe. I distance myself”

On question as to why he didn’t disclose what he knew sooner, he replies that he did. He spoke with journalists from two Johannesburg newspapers, The Star and Rapport. Both wouldn’t touch the story, describing it as too sensitive.

It appeared as if matters would lie there, but then a former RLI officer wrote a book called “The Search For Puma 164.” Lieutenant Rick van Malsen, later a captain the new Zimbabwe Army, was part of Operation Uric, an attack into Mozambique conducted by the most powerful force ever assembled in Rhodesian history.

This was in September of 1979, but by then uncomfortable reality had dawned on the Smith regime. It was losing the war despite all nefarious criminal effort.

The Lancaster House Conference was underway. Uric reflected yet another stillborn theory, in this case that a massive battle victory would strengthen the Muzorewa puppet hand in London.

What happened instead was that this mighty force limped back after being well and truly licked. Van Malsen, the book’s author who now lives in Botswana, exposed what Walls called “the official lie.”

It was that this mighty force had seen two helicopters shot down and seventeen white servicemen killed, but the “lie” was that the bodies had not been incinerated as claimed, but abandoned to rot.

This was of particular interest to Carton-Barber and was what enabled him to take Bate and Armstrong to court, but he mentions an official RLI response to the deaths of it’s own.

Armstrong was acting as the battalion commander, and although he made a regimental show at memorial services in places like Harare, he didn’t even bother to have a representative at Gweru and Kwekwe. Armstrong was one of those who made no proper effect to recover the Uric bodies, and was one of those who propagated “the official lie” about recovery being impossible

Nonetheless there was a Pretoria High Court link with the Operation Uric deaths and the earlier Operation Inhibit fiasco at Chicualacuala.

Two soldiers became separated from Carton-Barber’s column. This was due to thick bush, and although Carton-Barber initiated and participated in the successful return of the men, the mere fact of the separation resulted in accusation that he had betrayed a “sacred ethos” of not leaving men behind. He never took anyone to court in Rhodesia as he believed that this “sacred ethos” existed.

Then on reading the van Malsen truth behind “the official lie,” he realized that there really was no such ethos and never had been. Bate and Armstrong found themselves defending a court action for defamation and associated emotional distress

Both men were represented by Mr Ron Wheeldon, another former Rhodesian serviceman. The matter was heard by Mr Justice Avoukimedes on 24 October 2018.

He dismissed it on the purely technical ground of a South African court having no jurisdiction over anything that occurred beyond the country’s borders.

It appeared as if the war crimes that contextualized Carton-Barber’s treatment after Inhibit were about to slide forever into the dark depths of convenient forgetfulness . But then Bate made a huge slip

The case was a subject of some discussion amongst certain members of the “ex Rhodie” community, and Bate couldn’t resist to crow about the Avoukimedes judgement.

He made a public statement in which he accused Carton-Barber of perjury and ulterior motive. His false comments also were to the effect that Avoukimedes had ruled that Carton-Barber’s departure from the RLI was legitimate.

The statement was made in Johannesburg, and this time there is no question at all about a South African court’s jurisdiction.

Bate is one of those former Rhodesians living in the plush comfort of a Johannesburg suburb. He is one of that same ilk of men pretending to be war heroes despite a hiccup he is back in court.

Even though he stands there alone in the physical sense, he stands sharing in the overdue correction of misrepresented facts that shall help Zimbabweans better to gauge their tortured path to nationhood.

The war crimes that are part of Zimbabwe’s national heritage at long last are subject to the attentions of cold and clinical judicial scrutiny. The matter of Carton-Barber v Bate is much more than a defamation hearing in South Africa.

The Registrar of the Pretoria High Court is about to set a court date.-Reviewandmail