AS NELSON CHAMISA takes the stage in Karoi, a town in the north of Zimbabwe, he grasps a microphone with one hand and waves with the other. “Bye-bye, Zanu-PF, bye-bye,” he says. The 40-year-old leader of the MDC Alliance, Zimbabwe’s main opposition bloc, is a cocky speaker with a preacherly vibe. Switching between English and Shona, he scorns the party that has ruled Zimbabwe since he was two years old. He vows that the MDC will win elections on July 30th.

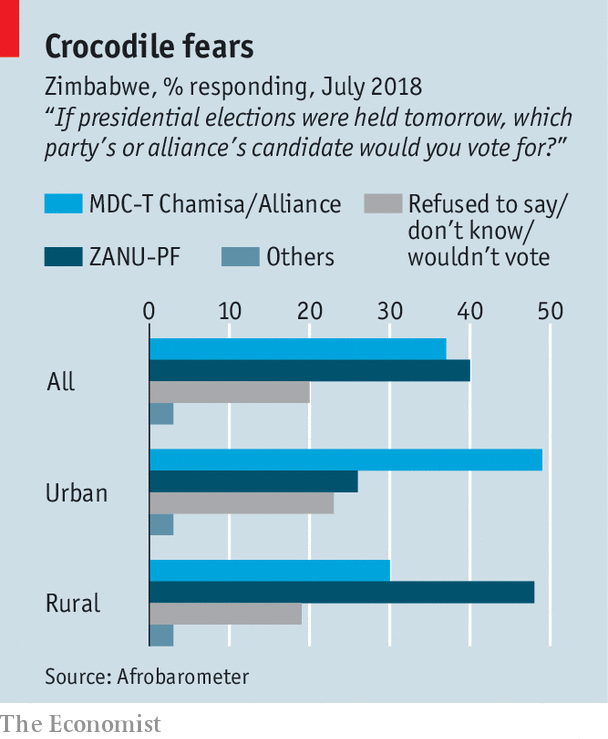

A few months ago most observers would have scoffed at his chances. President Emmerson Mnangagwa, the 75-year-old who succeeded Robert Mugabe after a coup in November, was going strong, strutting around foreign capitals declaring Zimbabwe “open for business”. But a poll released on July 20th by Afrobarometer found the MDC had closed the gap on Zanu-PF from 11 to 3 percentage points. The MDC was backed by 37% of respondents, with Mr Mnangagwa’s party polling 40% (see chart). Fully 20% were undecided or refused to state a preference. If most of these broke for the MDC it could at least force a run-off vote for the presidency, triggered when no candidate wins a majority in the first round. That outcome would lead to a period of profound nervousness, given how the army and Zanu-PF have previously chosen to murder and torture opponents rather than relinquish power.

Whether Mr Chamisa can upset the odds depends on two factors. The first is whether he is truly gaining support: two polls are a meagre basis for firm conclusions. More important is whether Zanu-PF will successfully rig the election.

There has not been a free and fair election in Zimbabwe for two decades. But hopes have been raised since the coup. Systematic violence is rarer. And freedom of expression has widened, at least in cities. Roland von Nidda, a Jesuit priest, says his congregation no longer shushes him when he preaches about corruption.

Some improvements notwithstanding, the vote does not look free or fair. Few Western observers believe that the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) is independent. The voter roll contains over 250,000 anomalous entries, according to Team Pachedu, a group of analysts. The oldest person in the world is apparently still alive—and keen to vote—at the age of 141. The ballot paper listing the 23 presidential candidates has Mr Mnangagwa conveniently placed at the top of the page.

Even if technical aspects of the vote were fair, Zanu-PF would still be able to use the power of the state to its advantage. It recently announced pay hikes for civil servants (17.5%), police (20%) and soldiers (22.5%). It has bought off or intimidated many traditional leaders. Food is being handed out at rallies. The party is lavishly covered by state television. Visitors to Harare, the capital, would be excused if they thought Mr Mnangagwa were the only candidate for president, such is his ubiquity on billboards.

Then there is intimidation. For example, local party hacks may threaten to harm rural voters if they vote for the opposition. We The People, a human-rights group, has reported at least 100 cases of abuse in each of the past two weeks. Many voters worry that they will lose their land if they back the opposition. According to Afrobarometer, 43% fear falling victim to electoral intimidation or violence.

The presence of observers from the European Union, American NGOs, the African Union and the Southern African Development Community should put a lid on more explicit chicanery. Mr Mnangagwa needs not just to win, but to win in a certified manner if he is to mend financial relations with creditors including the IMF.

The country is in dire financial trouble. Millions of people have emigrated. Between 1.1m and 2.5m of the country’s people may require food aid. Just 6% of the working-age population is in formal employment—the third most informalised economy in the world, according to the IMF. It is in arrears to the World Bank and the African Development Bank. Most African capitals are hives of construction; the only cranes in Harare are birds.

And it is beset by a growing currency crisis. Zimbabwe’s fiscal deficit was officially 13% of GDP in 2018; the real figure may well be higher, thanks to pre-election handouts. The government hoovers up all the American dollars (the country’s main denomination) it can find. In their place it issues “bond notes” and electronic deposits, which the state insists are of equivalent value. In effect, it is printing money while pretending not to. People on the street are not fooled. Bond notes trade at 1.35 to the dollar. Mobile money is worth even less.

“Money, money, money. It’s the problem,” complains Moleen Dzenge, who buys shoes in Zambia and sells them in Karoi. Her margins are being squeezed as the value of the money used by her buyers falls. So she is raising prices.

Inflation of imported goods is running at over 100%, estimates Eddie Cross, an opposition MP. Shops are raising prices or offering discounts to those with dollars, such as tourists or foreign correspondents.

Despite the mess, some parties think Mr Mnangagwa is best placed to mend the economy. These include the British and Chinese governments, and many commercial farmers and investors. Partly this reflects doubts about the MDC, but some outsiders think Mr Mnangagwa is a real reformer, despite his four decades at the centre of the regime that wrecked Zimbabwe. If he wins, many will declare the election free and fair enough, and move on.-Economist